Traditional arts and crafts have perhaps been the oldest industry. These crafts and art forms contribute to the Indian identity. They are a part of our culture, and that is something that will stay with us forever.” It was this sentiment that inspired Medhavi Gandhi to work for the welfare of India’s craftspeople.

The journey started when Gandhi, 24, worked as an intern on a UNESCO documentation project. “During this project I had to interact with artisans and craftsmen from South Asia. Most of them were Indian artisans. At that point of time, I felt quite embarrassed because I knew so little about the rich culture of our own country,” she says.

|

|

Potter Om Prakash with his 10-foot-high hookah that spreads awareness against

tobacco.

Photograph courtesy Happy Hands Foundation |

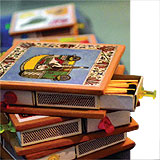

Matchboxes designed as souvenirs to celebrate the 100 years of Delhi.

Photograph courtesy Happy Hands Foundation |

|

|

|

The Happy Hands Foundation trains women in different crafts at the Dor Vidyalaya.

Photograph by Sakshee Chawla |

A T-shirt painting workshop with painter Siddharth GandhiPhotograph by Thivahar Bethune |

Gandhi realized that the middlemen who were involved in the crafts business often pushed up prices but the profit did not reach the artisans. And when cheaper knockoffs started selling more than genuine crafts, the artisans stopped innovating.

Gandhi’s response to this situation came in the form of the Happy Hands Foundation, which she started in 2009. “There have been many weaver communities—but what sets them apart is the weave, the pattern, the texture, the material—these form the identity of a clan [or] community,” she says. “The death of crafts would hugely impact the economy at the base level.”

|

|

A wooden temple, or kavad, opens up several folds to narrate a story.

Photograph by Thivahar Bethune |

Happy Hands Foundation volunteers display their products at a mall in New Delhi.

Photograph by Rishabh Chopra |

|

|

|

Medhavi Gandhi (right) with an artist at a Patachitra workshop in Orissa.

Photograph by Vinita Michael |

Photograph by Moitreyee Banerjee |

|

|

Happy Hands has helped artisans reach a wider market and reintroduced the usage of traditional crafts among young people through innovative, handcrafted games, jewelry and other collectibles.

Gandhi says her organization “empowers people by setting them free to explore different creative spaces. When someone knows they ‘can’ do something, they feel empowered. Even with our artisans, we host workshops where the concept is worked upon, but the real artwork is the artisan’s own creative mind. That definitely gives them the confidence to develop their own designs.”

Gandhi and her team work in villages, where artisans are trained to think about market needs and how their product can be developed further. The artisans are taught to keep in mind their community strengths and weaknesses, and how even though the villagers work on the same craft, they can be a little different from each other.

|

|

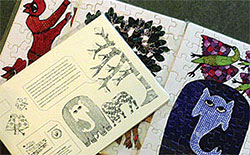

Gond

Art puzzles

Photograph courtesy Happy Hands Foundation |

Warli artist Ravi making a tray at his village in Maharashtra.Photograph courtesy Happy Hands Foundation |

“I think inspiring people has mostly come from involving them in the process…We did workshops with more schools, colleges; corporates understood they could explore more than just gifting with us, and I think that helped us do great work and set higher standards for ourselves,” says Gandhi. “We just happened to inspire people through our journey.”

Happy Hands works with artisans from states like Andhra

Pradesh, Orissa, Karnataka, Nagaland, Rajasthan, Delhi, Gujarat, Bihar, Maharashtra and Madhya

Pradesh. They work on pottery, crochet, cherial art, pithora art,

warli, madhubani, bamboo craft, Gond art, doll craft,

lacquerware, ikat, coir, dhokra, banjara jewelry, etc. The products are sold through exhibits, on

shopo.in, and through their outlet in New Delhi’s Hauz Khas village.

“We inspire people by involving them. People can volunteer to come for a Dor class—where we teach women how to do simple craftwork for livelihood. They can help us on an event, and witness the madness; or just spend a lot more time with us for artisan-related workshops,” she adds.

Gandhi says that she wants people to support the arts and crafts of India “because it isn’t just the form of art or the artisan but lives connected to the art that need attention. An artisan’s income impacts the future of his children, the health of his family, and so it is important to keep his art alive.”

Language was one of her biggest hurdles, apart from convincing the artisans to try something new. But, she says, these were hardly any obstacles considering what they usually face in the cities—lack of venues that allow them to exhibit or sell crafts, sponsor blues, etc.

Happy Hands worked with the New Delhi American Center in 2009 for Yellow Frames, a two-day film festival, panel discussion and puppet show. The festival highlighted the rise of Indian crossover cinema in the West and looked at the portrayal of Indians and Indian Americans through a Western lens.

Gandhi was also selected for the U.S. Embassy’s International Visitor Leadership Program in 2011. “The experience, needless to say, has changed some things forever,” she says. “There was a lot of learning, and some very fruitful collaborative ventures that have come about, thanks to the

IVLP.”

—Courtesy SPAN

|