INDIAN STORY IN FRENCH WEST INDIES

A pivotal look at how Indian indentured labour shaped the French West Indies

Turning to India

Initially, France turned to immigration from Europe, China and Madeira, without success. Following the example of its British neighbour, it then considered India, which presented numerous advantages. First, France already possessed five trading posts there, a situation that could facilitate the establishment of recruitment agencies; both climates were tropical; India was heavily populated and shaken by crises (famines, unemployment, drought) which constituted motivating factors for departure. Thus, between 1853 and 1889, nearly 68,000 Indian indentured workers flowed into the French Caribbean. There were 42,595 workers for Guadeloupe and 25,509 for Martinique. But how were they recruited?

It begins in the Caribbean. The General Council fixed the number of indentured workers needed based on the requests officially submitted by the planters. It then informed recruitment agencies established in the trading posts of Pondicherry and Karaikal, in southern India. These agencies relied on a network of Indian recruiters called “mestrys” or “kanganys” to approach populations who spoke little or no French. But language was not the only obstacle. The French trading posts were surrounded by a vast territory called the British Raj. The British did not want France to recruit labourers on its territory, as they claimed they needed them for the construction and development of their own infrastructure (railways, agricultural work, tea cultivation, etc.). However, thanks to the efficiency of French diplomacy, a convention was signed between France and England on July 1, 1861, thus allowing France to recruit more broadly.

Voyage and Arrival

Recruiters used all possible means to convince their audience (even getting them drunk). They evoked a land of abundance, close to India, where one could easily become rich. They were told that the return trip would be entirely covered once their contract was completed. This speech was enchanting, especially as it targeted the poor. They belonged mainly to the lower castes, the agricultural caste, and more rarely to the pariah caste. This immigration, although voluntary in most cases, remained a last resort, motivated by the hope of a better life.

It was in this context that, on May 6, 1853, after a three-month crossing, the ship Aurélie disembarked on the shores of Saint-Pierre, Martinique, with on board a contingent of more than 300 workers. The following year, on the night of December 24, 1854, this same ship would dock at the shores of Guadeloupe. The crossing was long and difficult as it generally took place aboard sailing ships; yet it is by no means comparable to the slave trade. Living conditions aboard the ship were strictly regulated. The good health of the passengers was a priority for the shipowner who received a bounty “per head” upon their arrival. Therefore, they received care from a doctor and were given varied food. The goal was indeed to limit the mortality rate during the crossing.

Harsh Realities

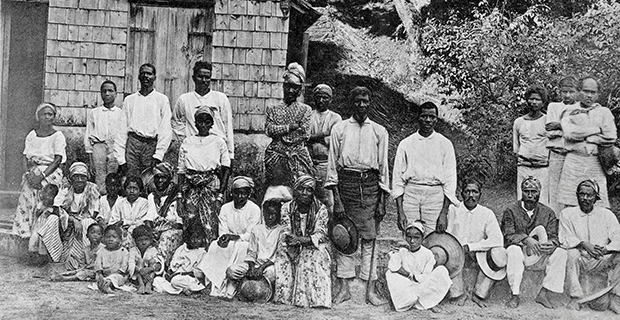

Upon their arrival, they were assigned a registration number and distributed among the plantations according to requests formulated by the planters. The contracts, signed in India, established six working days per week, twelve hours per day, for a monthly salary of 12.50 francs. The worker was to receive housing, clothing, and food. However, the planters rarely respected the contracts. No days of rest, endless days of labour, and little care given to sick or injured workers. Physical violence was not uncommon on the part of overseers who had not abandoned their slavery-era methods. A commission was supposed to monitor contract compliance and condemn the planters’ actions, but they were unfortunately often corrupted. Violence was commonplace and everything was a pretext for imposing salary deductions (work pace too slow, damaged equipment, injuries, illness, etc.). Moreover, indentured workers could not move outside the plantation without a pass signed by the planter. Working and living conditions far removed from the promises made by recruiters.

Comments.