INDIAN STORY IN FRENCH WEST INDIES

A pivotal look at how Indian indentured labour shaped the French West Indies

Resistance and Repatriation

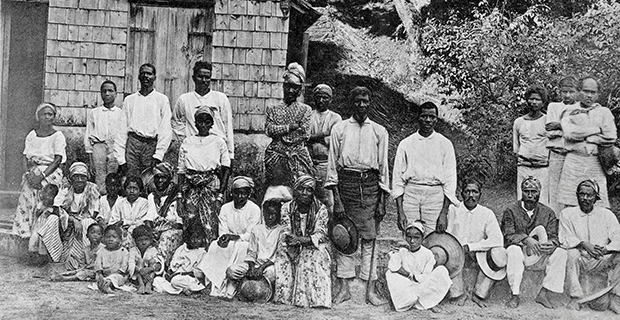

In response to mistreatment, acts of resistance emerged. Some fled the plantation and became mired in petty crime, others set fire to cane fields and sabotaged equipment. The most fragile developed drinking issues while some chose suicide to escape this hell. Historian Christian Schnackenbourg describes their conditions in these terms: “Four words characterize the living conditions of Indians on the plantation: discrimination, misery, violence, and disease.”

Why then so many chose to stay? The contract included repatriation of the indentured worker, his wife, and children, but he would lose this right should he remain in the colony without renewing his contract. The contractors would try everything to keep them in the colony. They maintained that the workers had to make up for days off when they were ill or injured. Thus detained, they missed the ship. Some stayed on the port for many months and, having spent their savings, had no choice but to sign a new contract. In contrast, the weakest, the sick, were crammed into unsanitary warehouses before being repatriated. It is one of the reasons why the mortality rate was higher during the journey back. Furthermore, the captain, receiving no bounty this time, provided no care to the passengers.

The first repatriations began in 1858. The crossing lasted between 100 and 150 days depending on the chosen route. Upon their arrival, the former indentured workers were examined by a French agent then by his British counterpart, if they had been recruited on British territory. Once this step was completed, they could finally return home. But time had passed, sometimes five years if not ten, and some no longer felt at home. Indeed, departure was poorly perceived in India, for both cultural and religious reasons: those who left had chosen to be away from their community, their ancestral land, and from their gods. But distrust was strongly fuelled by rumours about life in the colonies: workers were forced to practice another religion, to eat beef, and Indian women were prostituted. Because they faced rejection, no longer found their place within their family and community, some preferred returning to the Caribbean.

End of Immigration

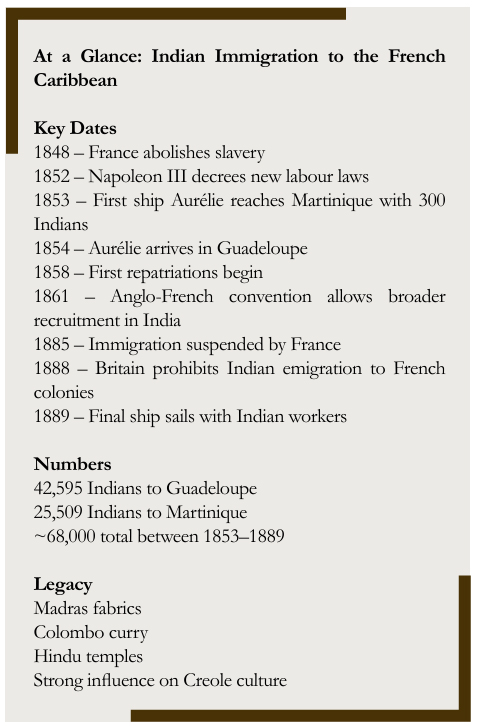

The year 1884 represented a turning point in Indian immigration. Some elected officials within the General Council wished to stop Indian immigration. It was presented as unfair competition to local workers whose jobs they took at low wages. It was also argued that Indian immigration was just another name for slavery. Indian immigration was finally suspended in 1885. Britain prohibited it in 1888 because of the mistreatment inflicted to Indian workers, most of them being subjects of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. A final ship was nevertheless allowed to travel to the Caribbean in 1889.

From the beginning of immigration to its suspension, 42,595 Indian workers had been introduced to Guadeloupe and 25,509 to Martinique. While we cannot say with certainty how many people of Indian origin are currently in the French Caribbean islands, we can nevertheless assert that they shaped the culture. From Madras fabric to Colombo curry, not forgetting the temples, India’s heritage can be seen in numerous aspects of Caribbean culture. Some would even say that it gave birth to creole culture.

[1] Extract from a petition addressed to the assembly of municipal delegates of Martinique to the Minister of the Navy and Colonies, signed by Le Pelletier du Clary, de Meynard, and Vergeron, in 1852-53.

Bibliography

- Farrugia, L. (1974). Les Indiens de la Guadeloupe et de la Martinique, A. P. Collet.

- Lasserre, G. (janvier-mars 1977). Les Indiens de la Guadeloupe. Cahiers d’outre-mer, n°117, (pp. 86-89).

- Singaravelou, (2000). Les Indiens de la Caraïbe, Tome 1. L’Harmattan.

- Leti, G. (2003). L’immigration indienne à la Martinique (1853-1900), Archives départementales de la Martinique.

Comments.